J. Fluid Mech. (2004), vol. 507,

pp. 255-264. © 2004 Cambridge University Press DOI:

10.1017/S0022112004009012 Printed in the United Kingdom

New solutions for capillary waves on fluid sheets

By M. G. BLYT H AND J.-M. VANDEN-BROECK

School of Mathematics, University of

East Anglia, Norwich NR4 7TJ, UK

(Received 16 December 2003 and in revised

form 11 March 2004)

The classical problem of nonlinear capillary waves

on two-dimensional fluid sheets is reconsidered.

The problem is formulated in terms of a complex potential, and solutions are sought using Fourier series expansions. A

collocation technique combined with Newton's

method is used to compute the Fourier coefficients numerically. Using this procedure, the exact solutions of Kinnersley (1976) are recomputed and various symmetric and antisymmetric

wave profiles are presented, including the limiting configurations which exhibit trapped bubbles of

air. Most important, three new solution

branches which bifurcate nonlinearly from the symmetric Kinnersley solution branch are identified. The wave profiles along these new branches do not

possess the symmetry or antisymmetry of the Kinnersley

solutions, although their limiting configurations

also display trapped air bubbles. No bifurcations are found along the antisymmetric Kinnersley solution

branch.

1. Introduction

Crapper (1957) obtained exact nonlinear solutions

for capillary waves on fluid sheets of infinite depth in terms of elementary

functions. His results demonstrated that

sharp troughs develop as the wave amplitude is increased until,

ultimately, a limiting profile is

reached with a trapped air bubble appearing at the trough. Beyond this point, the solutions intersect themselves and

must be discarded on physical grounds.

Later, Vanden-Broeck & Keller (1980) showed how

the solutions could be extended beyond

this limiting configuration by allowing the pressure in the trapped bubble to differ from the ambient pressure above

the fluid. With a view to modelling the effect

of a surfactant on the capillary waves, Vanden-Broeck

(1996) numerically computed new

solutions for variable surface tension using a collocation technique.

Taylor (1959) showed that small-amplitude surface

waves on thin fluid sheets can exist

either in a symmetric configuration, in which a trough on one surface opposes a

peak on the other surface, or in an antisymmetric configuration, where a peak faces a trough, and presented some experimental results. Kinnersley (1976) generalized Crapper's analysis to the case of fluid sheets of

finite thickness and obtained exact nonlinear

solutions, which are the large-amplitude analogues of Taylor's linear waves. Kinnersley derived a dispersion relation for the

finite-amplitude waves in terms of elliptic

functions and showed that it reduced to Crapper's result in the limit of infinite depth. For fluid sheets of finite

thickness, he demonstrated that a maximum wave amplitude is attained. Beyond this, the

solutions self-intersect and lose physical significance. Very few waves profiles are shown

in Kinnersley's paper, although the appearance of trapped bubbles is noted in the

limiting case of thin sheets. Kinnersley's results were rederived

in a simpler form by Crowdy (1999), who reconsidered

the problem using a new complex variable approach.

In this paper, we

readdress the

problem of capillary waves on fluid sheets of finite thickness. We recompute typical symmetric and antisymmetric wave profiles corresponding to the exact Kinnersley solutions, with a view to clearly demonstrating the shape of finite-amplitude wave profiles up to the

trapped-bubble limit. We follow

a numerical approach

based on an iterative point collocation method, adapted from that used by Vanden-Broeck

(1996). In particular, we investigate the possibility of solutions

without the symmetry or antisymmetry of the Kinnersley waves. A linearized analysis along the lines of Taylor

(1959) shows that, for small-amplitude waves, there cannot be an arbitrary phase shift

between the upper and lower surfaces, and only the symmetric and antisymmetric

solutions are possible in this limit. However, by numerically tracing the symmetric

solution branch into the nonlinear regime, we identify three new solution branches which emerge

as bifurcations at finite amplitude. Typical wave profiles along these new branches are

presented, and it is shown that along each new branch a limiting configuration

is reached which features trapped bubbles of air. No bifurcations are found along the antisymmetric solution branch. Our new solutions are reminiscent

of those computed by Chen & Saffman (1980) for pure gravity waves.

2. Problem formulation

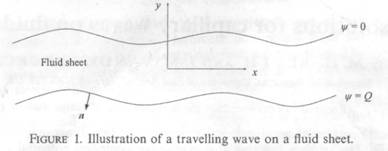

We reconsider the classical problem of a

two-dimensional -sheet of fluid of finit thickness, surrounded by air, on which a train of

periodic waves of wavelength A ar

travelling at a constant speed, as

shown in figure 1. We adopt a frame of reference ii which the fluid motion is steady. The fluid is

assumed to be inviscid, incompressible and irrotational, so that

the flow within the sheet is governed by Laplace's equation

We introduce a complex potential f = fi+ipsi, where fi(x, y) is the velocity

potential and psi(x, y)

is the stream function defined so that = 0 on the upper surface an( 1/r

= Q, with

Q < 0, on the lower surface. The wave speed c is

defined by taking the average

velocity u = grad fi over one

period of a streamline, so that

![]()

where dx

= (dx, dy). This implies

that when x varies by an amount A over a wavelength, then c varies by clamda. Since

the flow is irrotational, c is

the same for any choice of streamline.

Choosing f to be analytic inside the fluid domain, it only remains to satisfy the normal stress balance at

the upper and lower free surfaces. Thus,

it is required that

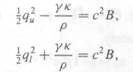

![]()

where p is the fluid pressure, pa is

the atmospheric pressure, y is the

surface tension, and

K = div n is the surface curvature, with n the unit surface normal pointing downwards. Applying Bernoulli's equation at each surface,

and using (2.2), (2.3), we have

(2.4)

(2.5)

where qt„ ql are the fluid speeds on the upper and lower surfaces

respectively, and p is the fluid density. The Bernoulli constant ccB is to be determined. Exact

solutions to this problem were given by Kinnersley (1976). These were later presented in a simplified form by Crowdy

(1999). In the case of a semi-infinite fluid sheet, exact solutions were obtained by Crapper (1957). We compute

solutions numerically using the collocation method of Vanden-Broeck (1996).

We work

in the hodograp coordinates (fi,psi ). Defining the velocity components u = fi,x v = fi,y our goal is to compute u — iv as an analytic function of f . All computed waves are symmetric about 0 = 0. Introducing tau(fi,psi) — itheta(fi, psi), defined so that

(2.6) ![]()

we may express the

surface curvature K as

(2.7)

![]()

Referring velocities to the wave

speed c and lengths to the wavelength A, we now write variables as dimensionless quantities and seek

solutions which are periodic in 0 with a unit period. According to the preceding definitions, (2.4) and

(2.5) become

where the dimensionless

parameter![]()

is defined by![]()

(2.8)

(2.9)

(2.10)

Following Vanden-Broeck

& Miloh (1995), we express the solution in the

form of an infinite

series,

(2.11)

where a0 and the coefficients an,

bn are to be found. Note that all of these coefficients are real. This follows from the assumed symmetry about 0 =

0. Previous workers (Taylor 1959; Kinnersley

1976; Crowdy 1999) have computed both symmetric

waves, where a trough on the upper wave

opposes a peak on the lower wave, and antisymmetric waves, where a trough faces a trough. For the symmetric

waves, by noting that

![]()

![]()

(2.12)

we see that the following relationship holds between

the series coefficients:

![]()

Similarly, for the antisymmetric waves, by noting that

![]()

a similar relationship holds, namely,

![]()

(2.13) (2.14) (2.15)

Two

distinct approaches to calculating the waves present themselves. First, we can adopt either of the formulae

(2.13) or (2.15) and compute symmetric or antisymmetric

waves. Second, we

can make no prior assumptions about the coefficients and confirm the

relationships (2.13) and (2.15) a posteriori. The latter approach leaves open the possibility of computing new

solutions without any assumed symmetries.

2.1. Numerical method

In practice we must terminate the

two series in (2.11) at a finite level. Fixing the surface tension parameter a, and truncating each series after N — 1 terms, we determine the 2N unknowns B, a0 and an, bn,

n = 1, ... , N — 1, by introducing N

collocation

points 0; along the

upper wave, and N

— 1 points 0;

along the lower wave, with

(2.16)

Consistent with the non-dimensionalization introduced above, the final condition comes from demanding that x change by a unit amount over one

period in 0. Thus, we

demand that

![]()

![]()

(2.17)

Substituting (2.11) into the Bernoulli conditions

(2.8) and (2.9) and condition (2.17) at each of the collocation points, we obtain 2N nonlinear algebraic

equations

for the 2N unknowns

iteratively using Newton's method.

To fully characterizethe solutions, we denote non-dimensional arclength along the wave by s and introduce the new dimensionless parameter T, defined on the upper surface ip

= 0 so that

![]()

The solution is

obtained

![]()

(2.18)

![]()

which

expresses the potential energy due to surface tension contained in the

distorted surface

(Schwartz & Vanden-Broeck 1979). In the case of a

flat surface, T =

O. With this definition, the dynamics is

described by the two free parameters a and T. Once a solution has been computed, x and y are obtained by integrating the identity

![]()

3. Results

A

first check on the numerical method is provided by recomputing

the exact solutions of Crapper (1957)

for waves on a fluid sheet of infinite depth. We obtained

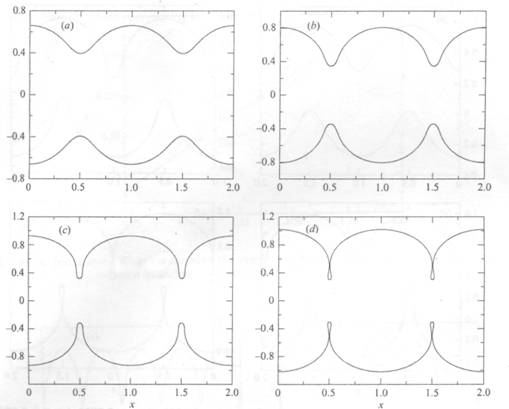

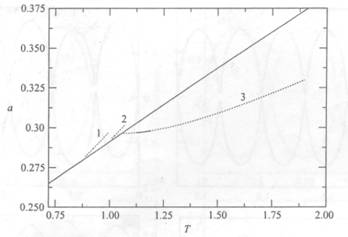

FIGURE 2. Q = —0.5. Symmetric

waves for (a) a = 0.1013, (b) a = 0.1154, (c) a = 0.12949,

and (d) a = 0.14103, the

limiting configuration with trapped bubbles.

excellent agreement with Crapper's

dispersion relation between the wave speed and the wave steepness, that is the difference in

height between a trough and a crest. To check the scheme for finite fluid sheets, the exact

solutions of Kinnersley (1976) were recomputed. In figure 2 we

display some of the possible waves in the symmetric configuration when Q = —0.5 for increasing values of the

surface tension parameter a. In

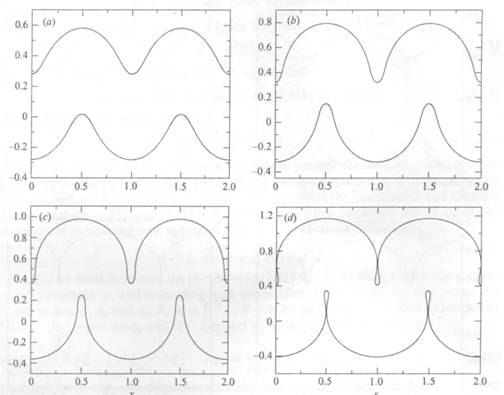

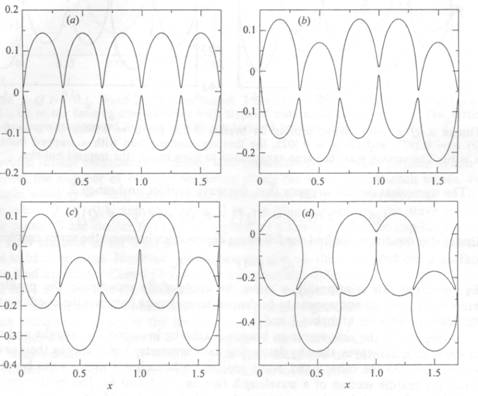

figure 3, some antisymmetric waves are shown for Q = —0.5 and various values of a. The numerical scheme was

implemented first adopting the relationships (2.13) and (2.15), and then under

general conditions. In the latter case, the relationships were confirmed numerically after

convergence. For both the symmetric and antisymmetric

waves, the

computations are continued up to the limiting configuration with a small trapped air bubble. Continuing

beyond this point, we obtain self-intersecting waves, which are of no physical

relevance. To demonstrate convergence of the numerics.

decay rapidly with n.

A linearized analysis along the lines of Taylor (1959)

reveals that, in the limit of small-amplitude periodic perturbations, only symmetric or antisymmetric disturbances are permitted. Therefore there cannot be an

arbitrary phase shift between the upper and lower surface waves. However, this does not prevent

other types of wave profile from appearing as nonlinear bifurcations from the symmetric or antisymmetric

![]()

we note that, for figure 3(a) where

with

![]()

we have

![]()

and so the

coefficients a„, b„

FIGURE

3. Q = —0.5. Antisymmetric

waves for (a) a = 0.1853,

(b) a = 0.2038, (c) a = 0.2223,

and (d) a = 0.2426, the limiting configuration with trapped

bubbles.

solution branches. To

investigate these, we follow the symmetric and antisymmetric

solution branches and look for

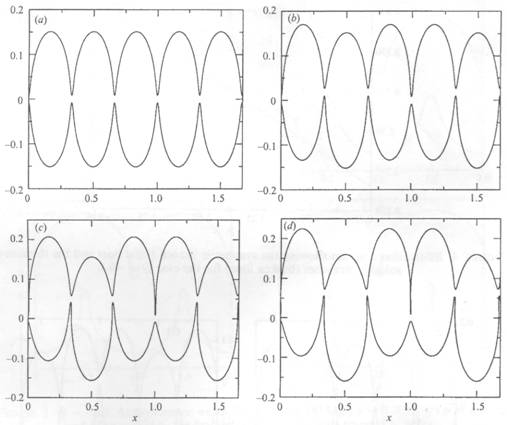

bifurcations at finite amplitude. Following the symmetric branch, we monitor

the sign of the determinant of the Jacobian matrix, 1 V II, where the gradient is taken with respect

to the unknowns fl. For illustrative purposes, we consider the case Q = —0.1.

As the surface tension parameter a is varied, the determinant changes sign three times

along the branch. This suggests the existence

of bifurcation branches (e.g. Keller 1977). By computing the eigenvector corresponding to the numerically smallest eigenvalue of the Jacobian matrix

at the point where the determinant

changes sign, and aligning our initial guess for Newton's method with this eigenvector, we are able to step

off the symmetric branch onto the new

solution branch. This procedure was repeated at the other two bifurcation points. The resulting bifurcation diagram is

displayed in figure 4. The new solution branches, which are shown as broken

lines, are continued up to the point where the corresponding wave profiles

exhibit a trapped bubble and thereafter self-intersect. We took N = 65 to

accurately resolve the more intricate wave profiles. For example, on branch 1 in figure 4, when a = 0.2870 we compute T = 0.8250

with N = 15, T = 0.9230 with

N = 35, T = 0.9238 with N = 55, and T = 0.9238 with

N = 65. For the simpler profiles,

far fewer modes are required. The wave profiles on branches 1, 2 and 3 can be

seen in figures 5, 6 and 7 respectively. Concerning secondary bifurcations from

these new solution branches, we note that the determinant of the Jacobian matrix remains

single-signed along each of these branches up to the point of self-intersecting

profiles.

FIGURE

4. Bifurcation

diagram showing the symmetric branch (solid line) and the three new

solution branches (broken lines) for

the case Q = —0.1.

FIGURE 5. Q = —0.1.

Wave profiles on branch 1 for (a) a =

0.2783, (h) a = 0.2794,

(c) a = 0.2840, and (d) a = 0.2943, the limiting

configuration with a trapped bubble at x

= 1.0. The vertical scale has been exaggerated to show clearly

the trapped bubbles.

FIGURE 6. Q = —0.1. Wave profiles on branch 2 for (a) a = 0.2900, (b) a = 0.2913, (c) a = 0.2977, and (d) a = 0.3025, the

limiting configuration with a trapped bubble at x = 1.0. The vertical

scale has been exaggerated to show clearly the trapped bubbles.

The numerical output suggests that, for wave profiles

on branch 2,

(3.1)

![]()

Under this condition, we find the

following dependence between the series coefficients:

![]()

(3.2)

By assuming this

relationship a priori, we

successfully recompute the profiles on branch 2. There do not appear to be simple

dependences between the coefficients for the wave profiles on branches 1 and 3.

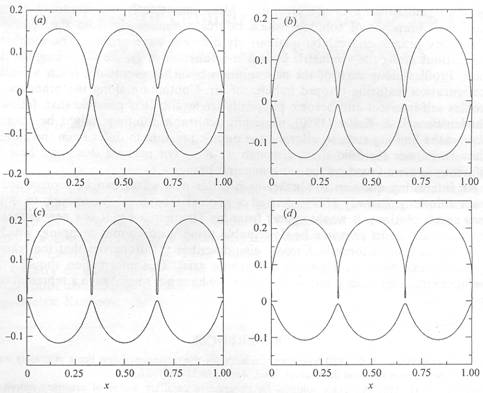

Topologically, the new waves on branch 3 arise by

lowering the troughs and crests of the symmetric waves, thereby

destroying their symmetry but retaining their original wavelength. On the other hand, wave profiles on branches 1 and 2 arise

by pulling down the middle section of

a wavelength (see figures 5 and 6). The main symmetric branch in

figure 4 has been computed so

that one period in 0 contains three wavelengths

(see figure 5(a), for example). As a result, the only non-zero coefficients an, b„ occur

if n

= 0 (mod 3). Computationally, there is the

possibility of obtaining new

bifurcation branches with topologically different profiles when m wavelengths are included within one 0 period along the main symmetric branch; in this case, the only non-zero coefficients occur if n

= 0 (mod in). However, our investigations have not

FIGURE 7. Q

= —0.1. Wave profiles on branch 3 for (a) a =

0.2960, (6) a =

0.2990, (c) a = 0.3083,

up to the limiting eonfiguration with trapped bubbles

at (d) a = 0.3176. The vertical scale has been exaggerated to show clearly the

trapped bubbles.

uncovered further bifurcation

branches with qualitatively new wave profiles. When Q is

varied, the number of bifurcation points along the symmetric branch varies. For

example, when Q = —0.4,

there are no bifurcations; there are two when Q = —0.2, three when Q

= —0.1, and one when Q

= —0.05. Interestingly, the wave

profiles along branch 3 are similar to

those computed by Crowdy (2001) for capillary waves on a fluid annulus in the limit as the number of

waves packed around the annulus tends

to become large. However, the surface tension on the inner

and outer surfaces of the fluid annuli for Crowdy's solutions are generally different.

We have also looked for bifurcations from the antisymmetric Kinnserley branch. The determinant of the Jacobian

matrix remains single-signed along the antisymmetric branch when m = 3, up to the limiting configuration

with a trapped bubble. The same is

true when in = 4 and m = 5. We repeated these calculations for several values of Q

with similar results. It would

appear that there are no bifurcations from the antisymmetric

branch, and hence no additional new solutions.

4. Summary

We have adapted the Fourier-series-based numerical

method of Vanden-Broeck & Miloh (1995) to

computing nonlinear capillary waves on fluid sheets of finite thickness. The numerical code was tested by recomputing the exact solutions of Crapper (1957) and Kinnersley

(1976). An assortment of profiles for both symmetric

264 M. G. Blyth and J.-M. Vanden-Broeck

and antisymmetric waves are presented. More importantly, we

identified at most three

new branches of solution, which bifurcate nonlinearly from the symmetric Kinnersley branch and exhibit qualitatively

different wave profiles. The number of bifurcations along the symmetric branch is a function of

Q, the flux along the fluid sheet. Profiles along each of the new solution branches eventually reach

a limiting configuration

featuring trapped bubbles of air. Continuing along the branches, the profiles self-intersect and become

physically irrelevant. It is possible that, following Vanden-Broeck & Keller (1980), physically

realizable solutions might be obtained beyond the limiting state by allowing the bubble pressure

to differ from the ambient pressure outside the fluid sheet, although we have not pursued this

point here. No bifurcations

were found on the antisymmetric branch.

An interesting

question is whether or not our new waves can be represented by exact solutions. Crowdy (1999) derived a general theoretical framework to

obtain such exact

solutions. It would appear from his Theorem 2.4 that our new numerical solutions should in principle be

describable using a conformal mapping, which is given by an explicit formula. Crowdy

also describes the properties that the relevant conformal mappings must possess if solutions exist.

This information should prove useful in obtaining exact solutions. However, we have not sought such a

representation here.

REFERENCES

CHEN, B.

& SAFFMAN, P. G. 1980 Numerical evidence for the existence of new types of

gravity waves of permanent form on deep

water. Stud. Appl. Maths 62, 1-21.

CRAPPER, G. D. 1957 An exaet solution for progressive

capillary waves of arbitrary amplitude. J.

Fluid Mech. 2, 532-540.

CROWDY, D. G. 1999

Exact solutions for steady capillary waves on a fluid annulus. J. Nonlinear Sci. 9,

615-640.

CROWDY, D. G. 2001 Steady nonlinear capillary

waves on curved sheets. Eur. J. Appl. Maths 12,

689-708.

KELLER, H. B. 1977

Applications of Bifurcation Theory. Academic.

KINNERSLEY, W. 1976 Exact large

amplitude waves on sheets of fluid. J. Fluid Mech. 77, 229-241. SCHWARTZ, L. W.

& VANDEN-BROECK, J.-M. 1979 Numerieal

solution of the exact equations for capillary-gravity

waves. J.

Fluid Mech. 95, 119-139.

TAYLOR, G. I. 1959 The dynamics of thin sheets of fluid. II. Waves on fluid

sheets. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 253, 296-312.

VANDEN-BROECK,

J.-M. 1996

Capillary waves with variable surface tension. Z. Angew

Math. Phys. 47, 799-808.

VANDEN-BROECK, J.-M. & KELLER, J. B. 1980 A new family

of eapillary waves. J. Fluid Mech. 98,

161-169.

VANDEN-BROECK, J.-M. & MILOH, T. 1995

Computations of steep gravity waves by a refinement of Davies-Tulin's

approximation SIAM J. Appl. Maths 55,

892--903.